Eight-year-old me circled Auntie’s bad words with a red pen.

—long words, foreign or fancy words, words beginning with X or V or with too many vowels, backsliding words, even words sometimes wondering why in bed late at night.

To earn my supper, I underlined the sentences that’d upset her.

—sentences about ill-fated marriages and earthly troubles, with women in skirts not below the knee, with children not fair or flaxen-haired and, therefore, prone to pick-pocketing.

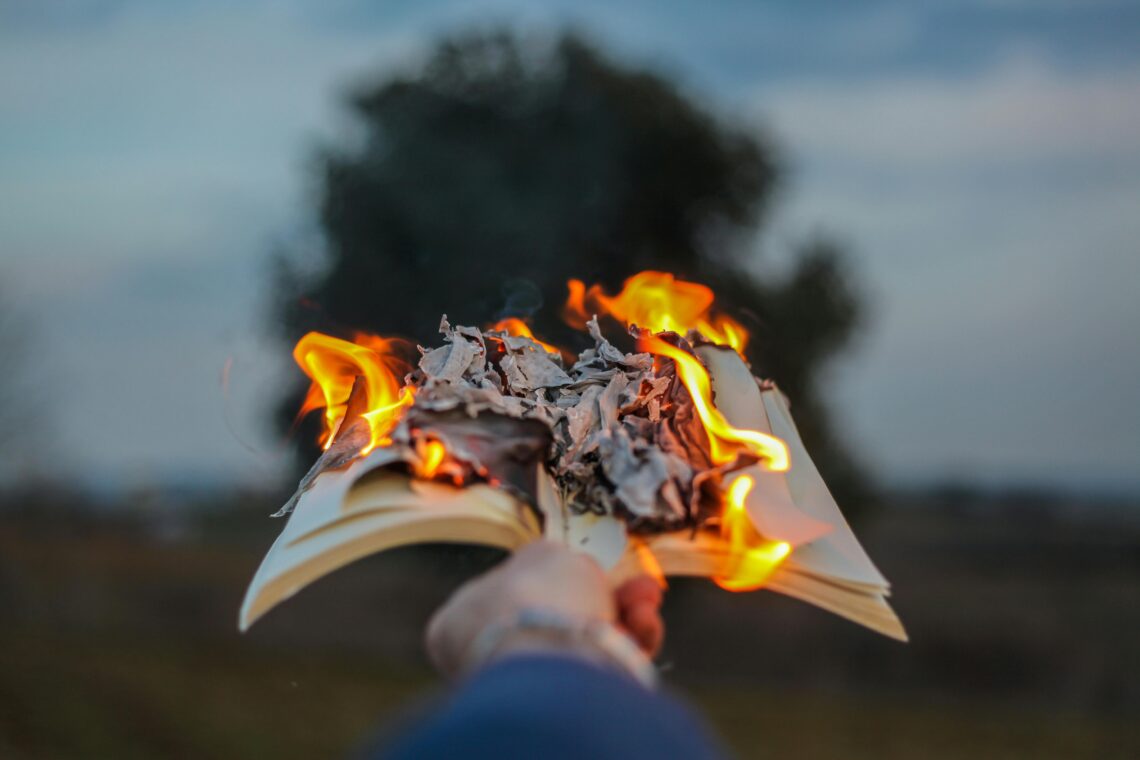

On the pages of stories indecent, I had to make an X in the top right corner. Left and low was wrong. Auntie intended to raise me righteous despite my dark curls and my father. There was cherry pie and a pat on the head if I frowned, tsk-tsked like she did, slapped my little unwashed hand over my mouth as I read.

—stories in which a man cried and a woman didn’t or something other than church happened on a Sunday, stories set in a far-away city more good than evil or in any heathen time.

I piled what Auntie made me do on the kitchen table. Under a big yellow bulb, she’d tear it all up, and fill a basket beside the woodstove. I fed it her approved disapproval.

When the cabin would fill with smoke, I blamed my tears on it and choked, No, Auntie, not crying. Nope. Not. The chimney must’ve been blocked.

So was her heart. Never red-hot, she was just grey and iron sure, her voice rusty like the little door I stuffed paper through.

Sifting through the morning ash, I’d compose fairy tales with the unburned bits before sweeping them into a bucket for Uncle. Then he’d say he was sorry about it, sorry that he and the last mule in the county had to plow my princely rescues and happy-ever-afters, witches and ancient children into the field. No giant beanstalk ever grew.

When the book shed was empty, I’d drive into town with Uncle. Brave the library—the staring and the whispering; had Auntie borrowed and never returned?—for its free book rack. We went to yard sales and charity shops, into dumpsters for anything that’d make Auntie smoulder and warm the cabin.

—books of poems that refused to rhyme and bundles of letters in handwriting that shook but told the truth no matter what, encyclopaedias—no one should know more than God, Auntie said—and old maps. Don’t try to run away.

I did.

How awful wonderful it is now. I write with a red pen. I write in a far-away city on a rooftop where there’s smoke and crying without excuse.

—a dystopian drama; set on a cold farm after all the paper has been burned; a man as tired as Uncle; every day, he searches the woods for a widow-maker to stand beneath so it’ll crash down and end him; doesn’t find such a tree; returns to his brittle wife with armfuls of twigs and dryly says, Maybe tomorrow; one day, he bursts into flame, saves the little girl; or perhaps it’s the wife who catches fire and the girl who saves the man.

Karen Walker (she/her) writes short in a low basement in Ontario, Canada. She has two tall dogs. Her most recent work is in or forthcoming in New Flash Fiction Review, Exist Otherwise, Misery Tourism, The Hooghley Review, Switch, and Does It Have Pockets?