by Jim Steinberg

In line at a polling place in Chapel Hill, an older man stands sideways four people in front of me. He waits and watches with a patience and curiosity no other early morning voter matches. His eyes are clear, observant, interested. I watch their dark pupils dance around the room and decide he would talk with anyone. But this crowd is impatient and inward, as if remaining aloof will hurry the procession through lines, registration tables, and voting booths to cars and freeway journeys. Like them, I came here enclosed in my cocoon, incubating myself for the daily rebirth of my work face. I want to complete this task and be on my way, but watching someone who seems to be here so agreeably changes that. I wonder if age explains his easygoing approach and if I will become as patient. If he were closer, I would talk with him.

I am certain he is Jewish. His nose crags outward a bit too far in a way not uncommon among Jews. In a way, I say to myself, because that caveat makes me more comfortable with my stereotype. I am a Jew, I say to myself, I am entitled to recognize another by his nose, though of course I could be wrong. I laugh at myself for this excuse that could work for any stereotype of any identity. I have others about Jews, and I enjoy them, too.

The old man is pleasant and warm and handsome, but more is going on here. Surely I stare as much at his Jewishness as at his welcoming face. I feel a connection so strong it unsettles me, and I know why. I have always been ambivalent about identifications that connect me with some and separate me from others. But here in the American Legion Hall, in line with so many strangers, I assure myself no harm can come. I give in to the connection.

I decide to give myself a generous allowance for sentimentality. The old man’s eyes contain a smile, a welcome he cannot escape offering. His bright pupils are mobile stations looking from still white ponds, periscopes from the bottom of his well. They move slowly about, waiting to greet. Shalom, they want to say. To anyone. They wait for contact, but in its absence seem content with watching.

Two lines crawl forward through the doors of the building in replication of the clogged highways everyone will be riding soon. “A through L” seems bottlenecked and slow to divide for the two registration stations reserved for it at the tables. By comparison, “M through Z” breezes by. The occupants of the slow lane show envy and disbelief.

“Same mistake every year,” says one. “You’d think they’d learn.”

“Splitting the population right down the middle of the alphabet clearly doesn’t work in this precinct,” says another. She shakes her head.

A few more remarks, half-smiles, light laughter, a few nodding heads. The stress of these folks seems to lessen, and they become more sociable. The old Jew begins to rotate slow half circles, trying, I think, to seize any opportunity for conversation.

Some Jews prefer a close identity. We are Members Of The Tribe, it goes. The Chosen. I’ve done none of this over the years, I haven’t approved. In my judgment that moniker, like so many others, elevates, separates, creates unbridgeable distance. I forget the centuries of experience that have forced many groups in on themselves behind circled wagons. Yet I pick from the crowd another Jew, though everyone in the room and in line all the way to the parking lot is responding to a call that should bind all of us together. Voting for shared participation in self government. For a moment my connection to that polity pales in comparison to the bond I feel with one stranger with whom I will probably never speak. Are we seeds from a single tree with roots in the ancient past, surviving in small, scattered groves all over the world? We are, but this should not be emphasized, I think. So many can say something like this. If you look at all history, how can you not see that ethnic, religious and national identity have brought us millennia of hate, warfare and persecution? Why is it so difficult for so many to see this commonality?

But I like staring at this handsome old man, and I like that he is a Jew. I don’t want a self-inquisition denying me this feeling of belonging that I don’t get enough of from the places where I think I should, like this so-called melting pot of America. I don’t want to soil this moment with doubt. Whatever this feeling is, it arises from within me like a spring welling up from some deep unquenchable source at the base of a wooded bluff. I want to feel that welling up. Is it knowledge as in getting to know, becoming better acquainted? Felt knowledge, a sixth sense so strong it should be added to the list of five? Or something I should cast away?

I ask myself how I can read so much into a nose?

His crags downward like an eagle’s, practically pointing to a little mouth that moves about with the slightest touch of impatience, more for lack of contact, I think, than for hurry, because our line is moving well. Or the little cleft in his square chin, a real Kirk Douglas dimple, a mark I’ve always associated with active men. He scrapes his perfect lower teeth against his upper lip, then purses his lips together, the tip of his tongue occasionally protruding, making a slow arc from side to side, a touch of impatience now. But he’s not hurrying to work, not in that knit short sleeve shirt, those Khaki shorts, that windbreaker tossed over his shoulder, those running shoes. He’s headed for tennis or racquetball, the gym, or the golf course. He’s finished with freeway drives to work. I envy him.

His body supports the inference that he is no aging couch potato. He is small but athletically built and postured. Straight-backed, trim in the belly, he stands at ease with legs apart, one hand clasping the other wrist behind his back. He rocks lightly back and forth from heel to toe like a referee on a basketball court waiting for the end of a timeout. Now he folds his arms in front and trades his rocking for twisting at his waist to the ends of his range of motion. His broad shoulders have no forward bend at all, his arms still have visible muscle. He has been doing something healthy most every day, swinging a racket or a golf club, using his trim legs to carry him as often as a car does. I want to look like that in twenty years.

His face is ruddy and tanned soft leather, a topography of smooth, shallow valleys, no rough wrinkles packed together. His hair is pure snow above a high forehead. His warm eyes carry the satisfaction of his years. The neat little creases radiating from the corners of those eyes looking for places to land.

I realize this is how I want him to be, that I am giving him an identity and wishing it for myself. Yet I think it’s true.

He is chatting now with a few complainers from “A through L” and doesn’t notice “M through Z” splitting as it approaches the volunteers who will verify our registration. In two steps I am next to him. He sees me, smiles, and returns to rocking forward and back. I see him davening in an Orthodox synagogue or at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, where I’ve never been. His smile continues through his rocking. He looks at me, a silent shalom without a question. He is as certain of me as I am of him.

“Are you a native of North Carolina?” he asks.

“No, a St. Louisan by way of Colorado and California.” My standard short-form answer.

“New York,” he says. “By way of Cleveland.”

“I can hear New York, just a bit.”

He smiles. “I don’t mind I still have it. What brings you here?”

The line is too short for more than a footnote. I give him highlights of my zigzag route to Chapel Hill through cities and careers. He smiles in recognition.

“Like my son. You’d tell me more if you had time. You must be going to work.”

An invitation, I think. “That is so. What brings you to Chapel Hill?”

“The city next door, Durham, the City of Medicine.”

“You must work at Duke Medical Center.”

“Not at my age.” He smiles. “My wife’s doctor does. A fine young man, about your age. Forty, forty-five.”

“Fifty, thank you.” I return the smile.

“A saint, this doctor. I love him. He keeps my wife alive and well. No small accomplishment. You would love him for that, right?”

“Absolutely.”

“I love him so much he keeps us from Florida. That’s where we thought we’d retire. But a doctor keeps your wife alive and well, you stay. Besides, Chapel Hill is better. A very nice place. But a person sees things differently when he has a good reason. You know?

“Yes, I know. We came here for my wife to return to school. It was her turn to make a change.”

“Good, very good.” He is rocking back and forth from the shoulders again, as if in prayer. I can almost feel mine begin. We fall silent and move forward, only two people left between us and the tables.

“He keeps my wife with me, this doctor,” he repeats, his voice deep in appreciation. “For this I love him.”

I slide to the left, avoiding the right branch of the split but am still beside him. A voice from in front of him asks, “Sir, could you give me your name and address?”

As he turns I see another volunteer waiting for me, a woman topped with a small blue-gray beehive, blue-tinted bifocals, blue eye shadow. A blue woman. I move toward her.

“I’ll spell it for you,” the old man says. “M-o-s-c-h-o-v-i-t-z, Saul, 1808 South Lake Shore Drive.”

“I’ll spell it for you,” I say to the blue woman before she can ask. The old man, ballot in hand, looks over at me. He waits.

“P-a-s-t-e-r-n-a-k, Louis,” I say. “2478 Foxwood Drive.” We are practically neighbors. The blue woman peers through the bottom of her bifocals and flips pages until she finds my name.

“Your ballot, sir,” she says. “Thank you for voting.”

“Thank you,” I say. The old man waits, watches. I think of my father who didn’t get to grow old, who never seemed particularly like a Jew, my agnostic, totally assimilated, urbane, sophisticated father. For a flash I miss him terribly. This man feels every bit as modern, yet more a Jew. For a moment I am a Member Of The Tribe. I don’t remember feeling strong about this. I decide to like it.

“Shall we?” Saul asks. We are going to do this together.

“After you,” I say. His smile broadens.

Once again, Saul rocks forward and back. I say to myself that he rocked like that on many a Saturday morning at an Orthodox or Conservative synagogue where a cantor sang the ancient rituals in the ancient tongue, no watered down Sunday morning ceremony at a Reform temple like the one I stopped attending as soon as I could, for want of feeling. I may be wrong now, it has been years, and I was a kid. He had Bar Mitzvah, I only confirmation to feel more like the Protestants across the street from Temple Israel. Though in all likelihood I would have tired of his synagogue as I tired of my temple, one thing is sure: I have not been to the spring, nor drunk there, like Saul has.

He turns slowly to the left and walks the twenty feet to the row of black-curtained booths. I follow him until we are side-by-side at two that are empty. He goes to the left, I to the right. At the same moment our left hands reach forward and part the curtains. We turn toward each other and nod a simple acknowledgement. I feel the warmth, but this time from within me as much as from him.

He extends a hand. “Moschovitz,” he says with a knowing smile.

“Pasternak,” I answer. I reach for his hand, squeeze it firmly, hold it a few extra moments, then let go slowly. With a final nod, almost a bow, we disappear into our booths.

I read the instructions on the ballot and follow them, filling in the boxes this time instead of punching holes. There is so much to vote on, so many ballot measures to properly identify. I try to hurry.

When I come out, Saul is gone. I think about going after him but decide against it. Now the place seems empty, or not a place at all, but I look at the crowd around me. Shalom, I say, and walk into the sunlight.

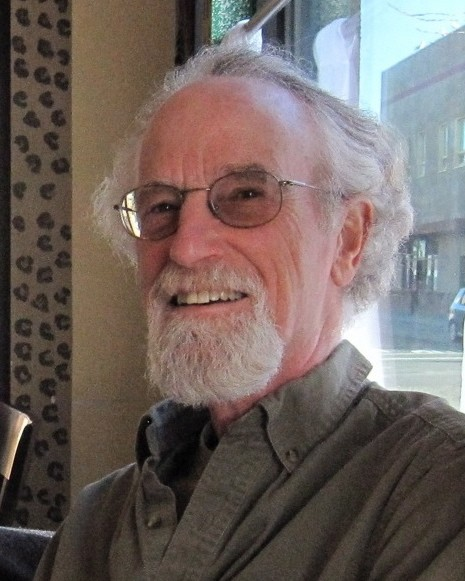

For thirty years Jim has written about family, love and work. Eleven of his stories have been published in literary journals. He has self-published Boundaries, a novel, and two collections of short stories, Filling Up in Cumby, Stories and Last Night at the Vista Café and Other Stories. His two-novel series, Third Floor, and Redemption, is looking for a home.